Mass detention in Belarus highlights growing tensions

Analysis. Around two dozen high-profile journalists were detained in Belarus in one of the biggest intimidation campaigns in years. Emerging details of this sudden and surprising sweep highlight growing tensions in the country, with its authoritarian regime seeking a balance between necessary pro-market reforms and the preservation of President Alexander Lukashenka’s autocratic rule. Meanwhile, there is a growing window of opportunity for the EU to influence pro-democracy processes in the country, with voices from civil society emerging at the bottom, and an attempted geopolitical shift away from Russia at the top, writes Maxim Eristavi, research fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Publicerad: 2018-08-24

How it happened

The detention of Belarusian journalists on suspicion of hacking the computer systems of state-run news agency BelTA started on August 7. By August 9, around two dozen of them had been detained and brought in for questioning by the Belarus Investigative Committee – the country’s main investigative law-enforcement agency, similar to the FBI in the US or the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND) in Germany.

Tut.by, one of Belarus’s largest online news outlets, became the primary target of mass detentions, along with the only privately run news agency, BelaPan, the academic newspaper Nauka, the real-estate news website Realt.by, and even the state-owned newspaper Kultura. Law-enforcement agents raided their newsrooms: at some (like Tut.by) they confiscated computers and laptops and detained staff; they allowed others (such as Kultura) to continue their work after the search.

Overall, 18 journalists were detained, including Marina Zolotova, Tut.by’s editor-in-chief, and Irina Levshiba, editor-in-chief of BelaPan. Additionally, the Investigative Committee detained Pavlyuk Bykovsky, correspondent for German broadcaster Deutsche Welle. Authorities seized his private and work equipment, including computers, his wife, Olga Bykovskaya, told Deutsche Welle. According to the Belarusian Association of Journalists, at least six apartments belonging to journalists were also searched as part of the operation.

By August 10, all detainees had been released and the Investigative Committee publicly promised to continue its investigation following the sweep.

Photo: Shutterstock

Yury Zisser, founder of Tut.by, confirmed that all his employees had been released, adding that the detentions were only a prelude, as the committee plans to take some journalists to court.

The crackdown provoked a wide range of international condemnation. The EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini, warned that “such actions contradict Belarus’ stated policy of democratization and its international commitments.”

In a more muted response, the US embassy in Minsk also expressed its “concerns.” In the US, the pushback from Congress was more vocal: the US Helsinki Commission Chair, Senator Roger Wicker, strongly condemned the journalists’ detention: “Lukashenka’s deliberate targeting of independent news outlets is an affront to the rights of the whole population,” Wicker said, calling on Belarusian authorities to “cease harassing those who dedicate their lives to uncovering and sharing the truth.”

German broadcaster Deutsche Welle said it had lodged a protest with the Belarusian ambassador in Berlin, Dzyanis Sidarenka, and demanded the immediate release of their detained reporter on August 8, the day he was taken into custody. The broadcaster stressed that the rule of law must apply to accredited journalists.

Svetlana Alexievich. Photo: Shutterstock

“This is an attempt to intimidate us all,” Belarusian Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich told RFE/RL. “There is a test: whether we exist as a society that is capable of offering civil resistance.”

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) urged Belarusian authorities to stop the “harassment of critical journalists.”

“Raiding newsrooms, detaining reporters, searching their apartments, and seizing their equipment are clear signs of a government crackdown on independent reporting, whatever the pretense,” the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), another global media watchdog, said in a statement.

“They showed me a search warrant and said that it’s linked to the case about illegal access to BelTA. They demanded that we switch off our phones. They didn’t specify who the search warrant was for and raided the whole apartment, including our daughter’s room.”

Olga Bykovskaya, a journalist and wife of Pavlyuk Bykovsky, a DW correspondent. Interview with Euroradio, August 10, 2018.

“After the search, they read me the indictment and we drove to Minsk. I was insisting on my right to a call, but they said I would be allowed to do it only after the search. However, I was denied the right even after that.”

Tatyana Korovenkova, BelaPAN journalist. Interview with Euroradio, August 10, 2018.

What are detained journalists accused of?

The Belarusian authorities accuse the journalists of illegally obtaining content from the paywalled services of BelTA. The Investigative Committee opened a criminal inquiry after an Interior Ministry investigation uncovered “15,000 cases of unauthorized access” to BelTA’s content. The committee claimed that “the crime inflicted considerable damage, leading to the illegal procurement and use of information protected from unauthorized access, as well as to the erosion of the enterprise’s business reputation,” a criminal offense punishable by a fine, a ban from certain professions, arrest, or up to two years in prison.

Authorities claim that the investigation was launched following a complaint from Irina Akulovych, BelTA’s editor-in-chief. “We have more than 30 subscribers among other newsrooms and I know them all. But there are those who didn’t subscribe, but still use others’ passwords to bypass the paywall. Naturally, we wouldn’t be able to investigate it alone. That’s why we filed a complaint with the police,” Akulovych told the local press.

Hours after the first detentions and searches, SB-Belarus Today, the presidential administration’s mouthpiece, published a detailed report exposing “the mass stealing of content from BelTA’s paid subscription.” It included a wiretap recording of Tut.by journalists acknowledging illegal access. Later they confirmed its authenticity. However, detailed content of the indictment has been published in violation of Belarusian law warning against disclosing the details of ongoing investigations.

Five signs exposing the intent to intimidate with this sweep

Amid a torrent of accusations from local civil society and human rights groups, the Belarusian government denies a political motivation for the recent raids and arrests. “The situation does not lie in the political dimension and has nothing to do with freedom of speech or journalists’ activities in Belarus,” the spokesperson for the Belarusian Foreign Ministry, Anatoliy Glaz, said in an official statement. However, there are at least five clear signs leading us to believe that this is an organized intimidation campaign by the government against the free press in Belarus.

Sign #1: The content of the case doesn’t hold up.

There is a huge gap between the content of the criminal code article used for the indictment and the alleged crime itself.

To justify the recent wave of journalist detentions, Belarusian authorities referenced article 349 of the country’s criminal code: “unauthorized access to information stored in a computer system, a network or on any other device, which is accompanied by a violation of the system’s protection, resulting in inadvertent modification, destruction, blocking of information or destruction of computer equipment, or causing other significant harm.” To put it simply, the article describes a hacker attack. Judging from the available evidence, law-enforcement statements and the testimonies of the detained, the BelTA case shows no signs of being a hacker attack. Instead, journalists are accused of accessing paywalled BelTA content using logins and passwords illegally shared with them. “If indeed they just used someone else’s login credentials to access paid newswires, this does not constitute a hacker attack and is not a good body of evidence for a criminal act,” Sergey Zikratskiy, a Belarusian lawyer, confirmed in an interview with Euroradio, the country’s largest independent radio station.

Sign #2: The wiretapping of accused journalists started before the official investigation was launched.

The accused journalists featured in the aforementioned wiretap, in which they admit that they are at fault, confirm that it dates from no later than March 2018. But according to an investigation by local independent journalists, the official probe into the case was launched no earlier than April 2018 – weeks later. Authorities did not disclose exactly when they started wiretapping the journalists, and on what legal grounds, raising concerns that the whole operation might have been a trap.

Sign #3: The accused journalists didn’t do anything new or unusual, similar practices can be found around the world.

Although indeed questionable, circulating one set of login credentials for paid subscription newswires among multiple non-subscribers is a widespread practice, not only in Belarus or Eastern Europe, but among many journalists all around the globe. In countries with restricted press freedom or an underpaid newsroom workforce, there is an additional element to it: a monopoly of state- or oligarch-owned news agencies on information coming from government officials and institutions. When I started working as a young journalist in Ukraine in the early 2000s, my colleagues and I, often harassed by the authorities and underpaid by employers, would use newswires with exclusive access to the ruling elites in the same way. Belarusian journalists face the same choice in 2018: the state-owned BelTA has exclusive access to the Belarusian authorities and a monopoly on breaking news or reporting on government activity. “In this situation local non-state media have no other choice than quoting state-owned agencies that work closest to officials. This is a completely abnormal situation, causing distortions in our media market and leading to incidents like the BelTA case,” warnsLeonid Fridkin, a Belarusian media observer.

“It’s a shame that the authorities are using BelTA to prevent our independent news agency from doing its work. BelaPAN has legally used BelTA open-access information and always cited it with references and hyperlinks to the state agency’s original reports. We had to do it, because we don’t have the same access to official news about the president and governmental agencies.”

Iryna Lewshyna, BelaPAN editor-in-chief, one of the detained journalists. August 7, 2018.

Sign #4: Extra-long detentions are unusual for this kind of criminal offense.

At least eight of the 18 targeted journalists were detained for 72 hours. Belarusian authorities reserve this kind of extra-long detention only for criminal cases where jail terms of longer than two years are likely. However, article 349 of the criminal code used for indictment in this case indicates a maximum jail term of two years. This additional procedural element exposes the political nature of the BelTA sweep.

Sign #5: Increasing competition between state-run and independent newsrooms in Belarus.

Mass detentions and searches at independent Belarusian newsrooms coincide with the expansion of their audience compared to BelTA. At the moment, the online audience of Tut.by is 46 times bigger than that of BelTA. Another targeted newsroom, BelaPAN, is a privately-owned direct competitor of BelTA. Unlike both independent newsrooms, BelTA often reports favorably and uncritically on President Lukashenka. The ongoing case will seriously disrupt the work of BelTA’s independent competitors.

“I knew what a shock it must have been for them. But when you’re a journalist and you don’t work for government media, you should still always be ready, even though it’s hard to comprehend that you can be arrested for just being a journalist simply reporting what is going on, reporting reality.”

Natalia Radzina, editor-in-chief of the banned independent news website Belarusian Partizan. RFE/RL, August 8th, 2018.

Why it matters

Reason #1: Independent Belarusian journalism is getting louder and the authorities’ attempts to quash it is yielding diminishing returns.

Since its independence in 1992, Belarus has been one of the most hostile places for journalists in the world: it ranked 155th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2018 World Press Freedom Index. In recent years, President Lukashenka has been emulating many censorship tactics from the neighboring regime of Vladimir Putin in Russia. For example, since December 2014 Belarusian websites can be blocked without a court order. The legal definition of “mass media” was expanded and liability for content was widened to include user comments. A state commission was established in August 2014 to evaluate whether media outlets contain “extremist” materials that could be banned under a 2007 counter-extremism law – a popular security framework cover-up for suppressing press freedom among autocratic regimes in the region and around the world.

Anti-government protests in Minsk, March 2017. Photo: Shutterstock

However, rising public discontent in the last year provoked mass demand for unbiased reporting. In the spring of 2017, President Lukashenka introduced a tax on those who are not employed full-time in an attempt to boost the country’s faltering, largely unreformed economy. Rarely seen anti-government protests filled public spaces across the country. Major anti-government demonstrations expanded the pool of independent journalism in the country, fueled by opportunities provided by still-accessible social media platforms. The Belarusian authorities have stepped up their pushback, blocking leading news websites, adopting an even more draconian media law and subjecting independent journalists to unprecedented wave of fines. In June 2018, Belarus’s parliament passed amendments to the country’s media laws to combat “fake news.” CPJ said the amendments are likely to lead to further censorship of the press in Belarus. Earlier this year, a prominent Belarusian journalist was sentenced to four years of forced labor for critical coverage of the government and four journalists from Belsat, the only independent TV station, went on trial and were heavily fined for the same “offense.”

However, the 2017 crackdown failed to reach the level of the previous one in 2011. A record number of people tuned in to live streams of the protests, with some of the journalists managing to broadcast during detention, even from within police stations. This was the first time that Belarusian journalists managed to be so audacious, working in the same way that journalists in democratic countries do, admitsViktar Malishevsky, editor-in-chief of the country’s biggest independent radio station.

Reason #2: The ruling regime in Belarus cannot afford harsh crackdowns on the free press anymore.

This is where neighboring Russia comes into focus. President Lukashenka’s Belarusian regime is forced to use local media space to counter increasing Russian propaganda warfare against the country.

Following intensifying Russian aggression against former colonial territories that resulted in the invasion of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, a petrified Minsk decided to rein in its economic and political dependence on Moscow and take a friendlier approach not only to Ukraine, but to the West and China. In response, Russia has revved up its notorious propaganda and disinformation machine to ensure Belarus keeps its distance with regard to the outside world. It forced President Lukashenka into a “necessary evil” compromise: Zisser says that authorities tolerate Tut.by’s moderately critical coverage because they know readers would turn to more radical foreign-based sources if the site were not allowed to operate. This tolerance, however, does not fully protect Tut.by’s journalists, as the recent intimidation campaign suggests. At the same time, in 2017 the authorities allowed the return of several independent print newspapers to state-owned newsstands. Almost two dozen newspapers were banned from state-owned press distribution networks just before the presidential election 11 years ago. Their successful return is attributed to a meeting between President Lukashenka and the editor-in-chief of the pro-opposition newspaper Narodnaya Volya in February 2017. State distribution networks are now openly cooperating with both Narodnaya Volya and Nasha Niva, the country’s leading opposition print publications.

Reason #3: The recent crackdown suggests the Lukashenka regime feels freedom of speech is developing too quickly amid unprecedented pro-market reforms.

The growing voices of independent journalism and civil society do not exist in isolation from other profound changes occurring in Belarus. Following a geopolitical shift away from total dependence on Russia, the government also embarked on bold pro-market reforms. The Soviet-era economy had run its course by the early 2010s. Falling oil prices and economic turmoil in Russia, exacerbated by the country’s aggressive military advances, forced Belarus to look elsewhere for aid – the IMF bailout talks were restarted in exchange for economic reforms. The liberalization of the Belarusian economy in the last three years ended a deep recession, resulted in the historic cancelation of short-term visas for citizens of 80 countries, started one of the biggest IT industry booms in Europe, pushed the country into the top 40 of the World Bank’s Doing Business index, where it occupies the sixth position among former Soviet states. Minsk is changing fast too – there’s a boom of hipster cafes, restaurants, and art spaces. However, calling Belarus “Europe’s Singapore” would be premature for now, many analysts warn. The pace and depth of reforms are not yet sufficient, and economic dependence on Russia remains substantial.

How the recent crackdown on Belarusian journalists corresponds with regional trends

The crackdown on independent journalists in Belarus fits the regional trend neatly.

With a tightening “authoritarian belt” around Europe, reinforced by illiberal or authoritarian regimes in Russia, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Hungary, press freedom is under increasing pressure. International hunts for dissidents by the Turkish and Azerbaijani governments compromised the law-enforcement and justice systems of many emerging democracies in the region. Ukraine violated international law by extraditing Turkish or detaining Azeri dissident journalists. A prominent Azeri journalist in exile was recently kidnapped in Georgia and shipped back to Baku to face a politically motivated trial.

In Ukraine, journalists are beaten every four days, with violence against them becoming normalized and going totally unpunished. There has been zero progress in the investigation of the murder of prominent Belarusian journalist Pavel Sheremet in Kyiv in 2016.

During Putin’s 18-year rule, press freedom in Russia has sunk to its lowest level since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Being a journalist in Eastern Europe in 2018 is increasingly an act of everyday life-endangering bravery, regardless of whether a country is democratic.

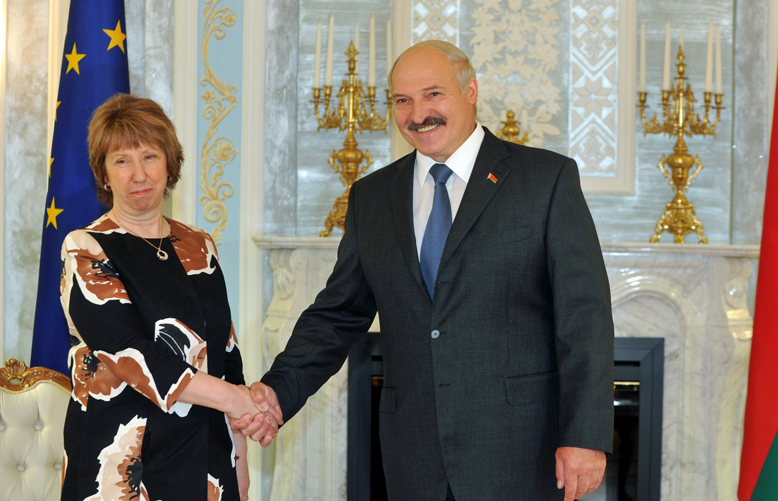

Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenka shakes hands with EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Catherine Ashton in Minsk, August 2014. Photo: Viktor Drachev/EEAS/Creative Commons

Leverage the EU and European democratic states have in pushing back against crackdowns on liberties in Belarus

Unprecedented.

President Lukashenka’s ongoing economic reforms and geopolitical shift away from Russia is not a choice, but a necessity allowing the regime to survive and adapt to growing expectations from regular Belarusians.

The following months will only exacerbate growing tensions between Russia, which compensates for economic turmoil with doubling down on aggressive colonial rhetoric, and the Belarussian regime trying to reclaim more autonomy from Moscow. “We are going through a difficult period now – Russians are acting in a barbaric way towards us. I say that publicly,” BelTA quoted Lukashenka on August 10. “They make demands like we are their vassals.”

The row creates a unique opportunity for EU states to enter into a strategic alliance with Belarus to counter Russia’s increasing political and economic meddling in European democracies. This alliance won’t bring an overnight change to autocratic Belarus, but it will reinforce those positive steps that Belarusian civil society has already taken towards a more open country.

Economic reforms, a stronger voice for the independent press and civil society, even the fact that the ongoing intimidation campaign against journalists is much less harsh than in 2011, are signs that Belarus is moving in a promising direction. The BelTA crackdown is a simple reaction of an authoritarian government to the speed of positive transformations, but it doesn’t have the capacity to reverse them at the moment. None of it would be possible without the recent rapprochement with the EU that lifted harsh economic and political sanctions against Minsk in 2016. Some EU states amplified it with additional friendly steps towards Belarus: after a six-year hiatus, Minsk reappointed the ambassador to Sweden, noting that “the Ice Age in relations between Belarus and Sweden has officially ended.”

Now is the time for the EU to double down on the carrot approach, while also rolling out the stick element: the increase of further political and economic support (including through the IMF framework) must go hand in hand with more forceful corrective measures in case of pushback from the entrenched elites against pro-democratic changes. In light of deteriorating relations with Russia, Belarus might easily become a new ally of European countries guarding themselves from increasingly aggressive meddling from Moscow. But this alliance cannot compromise the foreign policy values shared by the European community of states and must be based on smart conditionality: President Lukashenka must allow further pro-democratic changes in Belarus if he wants more EU support.

“What is happening at the moment is not a regular conflict of two business enterprises. These actions have an effect on freedom of speech in Belarus, they spread fear. Belarusian journalists have a sad joke: editorial freedom in Belarus extends to the number of minutes needed for the police to get to a newsroom. And this is the reality we live in: at any point they can storm through your door and do anything they like.”

Pavlyuk Bykovsky, detained DW correspondent in Belarus. August 7, 2018.