Historical Revisionism in Russia and Turkey

Analysis. Like his counterpart in Russia, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is looking for a historical role model that can help him justify cloaking his presidency in regal trappings. And like Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Erdogan is bypassing the revolutionary and republican eras, and focusing on the late imperial period. Putin’s new favorite role model seems to be Tsar Alexander III (r. 1881-1894). For Erdogan, it is Sultan Abdulhamid II (r. 1876-1909), writes UI Senior Fellow Igor Torbakov.

Publicerad: 2018-03-22

In September 2016, speaking at a symposium commemorating Abdulhamid II's birth, Ismail Kahraman, a ranking member of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) and speaker of the Turkish parliament, described the sultan's reign "as a mariner’s compass [for Turkey] to give us direction and enlighten our future.”

Arguably, Abdulhamid is one of the most controversial rulers out of all 36 Ottoman sultans. Turkey’s Islamists hail him as Ulu Hakan (Sublime Khan) – a pious autocrat who ruled the vast empire with an iron fist, standing up to infidels and keeping the Ottoman domains together through the skillful deployment of pan-Islamist ideology. For Turkey’s secularists and Westernizers, Abdulhamid is Kizil Sultan (Red Sultan) decried for his tyrannical ways, obscurantism and bloody suppression of Ottoman Armenians.

Not unlike President Putin, who clearly identifies with Tsar Alexander III, Recep Tayyip Erdogan seems keen to emphasize similarities between his policies and those pursued by Sultan Abdulhamid II at the turn of the 20th century. Referring to Payitaht—Abdulhamid (Capital City—Abdulhamid), a popular TV series that tells the story of the sultan’s last years on the throne, Erdogan noted that “the same schemes are carried out today in exactly the same manner. The West’s moves against us are the same. Only the era and the actors are different.”

Payitaht, which has been broadcasting for almost a year on the state broadcaster TRT, is a classic example of historical revisionism, under which the past is shamelessly manipulated to meet the current political needs of incumbent authorities. The series portrays Abdulhamid II as a virtuous ruler who was going out of his way to preserve law and order in his sprawling realm. His main adversaries were the predatory European great powers pursuing their nefarious designs through the Ottoman Empire’s “fifth columnists” – liberal intellectuals, Freemasons, and Zionists. It was those unpatriotic Western proxies, the TV show appears to suggest, who were largely responsible for the empire’s disintegration.

The mausoleum of Sultans Mahmud II, Abdulaziz and Abdulhamid II in Istanbul. Photo: Shutterstock

The present-day official glorification of Abdulhamid II is one outcome of a decades-long process of history rewriting by Turkey’s Islamist authors. Most prominent among them was Necip Fazil Kisakurek (1904-1983), an anti-Semitic poet, novelist and Islamist thinker who sought to replace the Kemalist secular notion of nationalism with an Islamist one.

Kisakurek considered Abdulhamid as his “historical friend,” who, as caliph, struggled to keep the empire intact. Conversely, Kisakurek had no love for secularist republicans, who, in his view, accepted the loss of empire, abolished the caliphate, and suppressed pious Muslims as part of a ruthless program of social engineering. Kisakurek contended that “understanding Abdulhamid is the key to understanding everything.” The implication is that one’s stance toward the late Ottoman sultan is a defining factor in that particular individual’s political and religious orientation.

It would appear that Erdogan has been deeply influenced by Kisakurek’s writings and, in particular, by his interpretation of Abdulhamid’s reign. Some analysts even called Kisakurek “Erdogan’s muse.” The Turkish president, who met Kisakurek and attended his funeral at the dawn of his political career, has himself acknowledged the Islamist poet’s intellectual influence on his personal development. Speaking on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of Kisakurek’s death in 2013, Erdogan described his life and work as a “guide for himself and future generations,” adding that the writer “helped us, like no other, to make sense of history and the present.”

The monument to Alexander III in Livadia, Crimea. Photo: Shutterstock

Both Putin’s Russia and Erdogan’s Turkey appear to be particularly attentive to matters pertaining to what might be termed the “sacred geographies” of empire. After the 2014 annexation, Crimea has become one of the most important sites in Russia’s symbolic geography. It was designated as a holy place where Rus’ was baptized when its ruler had accepted the light of Orthodox Christianity from Byzantium. Chersonesus on the outskirts of Sevastopol has now eclipsed Kyiv and the Dnieper River where generations of historians had previously located Russia’s principal “baptismal font.” The Livadia monument to Alexander III is meant to highlight the Romanov dynasty’s connection to the peninsula and further underscore Crimea’s symbolic significance for Russia.

Likewise, it is impossible to understand Erdogan’s interest in Syria (and especially in its capital Damascus) without taking into account the current Turkish leadership’s neo-Ottomanist ideas and its reverence of Abdulhamid II, who happened to be particularly sentimental about Damascus as a symbolically important transit point on the hajj route to Mecca.

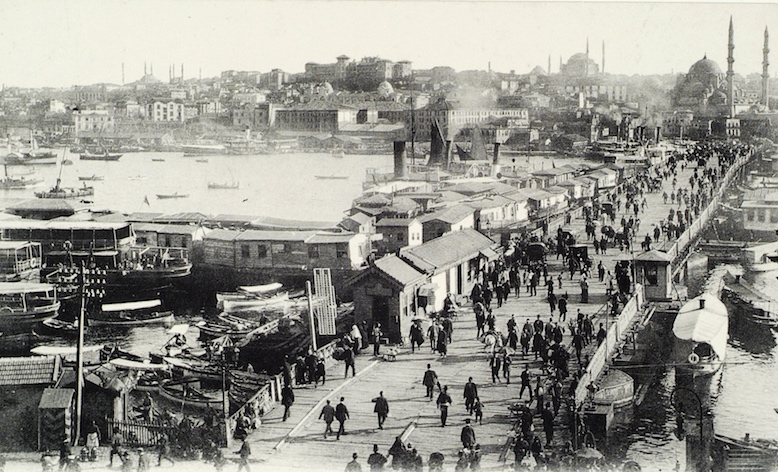

Istanbul, circa 1900. Photo: Shutterstock

It is not unusual for present-day leaders to look for a “Golden Age” in their nations’ past and then use it as a template and/or a kind of allegory of their own times. It is also quite understandable why Putin and Erdogan look wistfully at the late imperial period in the history of their countries. Given both leaders’ authoritarian tendencies, they find quite appealing what they believe were the most characteristic features of the reigns of their respective royal role models – Alexander III and Abdulhamid II: the unchallenged authority of an autocratic sovereign, the transformation of a multi-ethnic realm into a “national empire,” and a state exuding proud nationalism with highly pronounced anti-Western connotations.

Yet this is an oversimplified vision of Russia’s and Turkey’s respective pasts. Ultimately, both the Romanovs and the Ottomans failed to meet the challenges of modernity. Historical revisionism that produces the idealized images of late imperial periods will hardly help these two countries to cope with the challenges of the globalized world of the 21th century.