Russia and China: diverging partners in Eurasia

Interview. Russia and China are two important players on the Eurasian continent that have had different approaches to the concept of Eurasia on several occasions. UI’s intern Anna Zotééva spoke with Igor Denisov, a Russian expert on Russia-China relations, about Russian-Chinese cooperation in the Eurasian region and prospects for the future.

Publicerad: 2019-05-23

Igor Denisov, one of Russia’s leading experts on China, believes that there is a difference in how Russia and China define the geographical space of Eurasia. In the Chinese view, Eurasia is limited to the post-Soviet states, and the Eurasia department at the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs works towards the countries of the former USSR (with the exception of the Baltic States). Moscow’s notion of Eurasia is much broader: it comprises basically all countries on the Eurasian continent, including e.g. Western Europe and South Asia.

“Although there is no policy document in Russia that defines the Eurasian region, the concept of Eurasia has been introduced into policy vocabulary,” says Denisov.

Igor Denisov. Photo: UI

Igor Denisov. Photo: UI

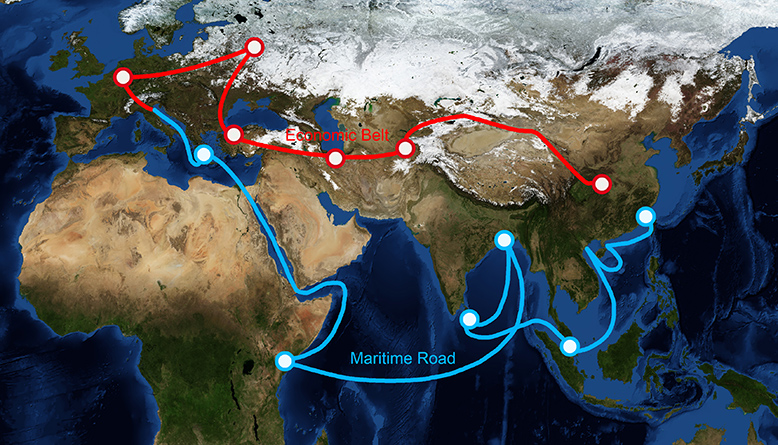

In 2015 Russia and China agreed on a joint declaration to coordinate the European Economic Union, EEU, (Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan) and the Silk Road Economic Belt (an overland part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, BRI). The parties acknowledged the importance of each other’s initiatives and agreed on further alignment between them. This agreement was the beginning of the so called Eurasian Economic Partnership that should be distinguished from the Russian concept of Greater Eurasia: whereas the Eurasian Economic Partnership implies a more tangible trade and economic cooperation between Russia and China, the concept of Greater Eurasia aims at eliminating dividing lines across the Eurasian continent.

Today, Russia and China are negotiating a trade treaty within the framework of the Eurasian Economic Partnership. However, the fact that Russia cannot adopt a free trade zone with China without the participation of the EEU should not be neglected.

“This proves the EEU is not a Moscow-dominated neo-Soviet political union. Without the will of the EEU Russia can only take decisions on minor matters, such as tariff barriers,” says Denisov.

Meeting of the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council in St Petersburg, December 2018. Photo: Kremlin.ru

Meeting of the Supreme Eurasian Economic Council in St Petersburg, December 2018. Photo: Kremlin.ru

Although there is an opinion that political aspects of integration, such as security and defense issues, are more important to Russia, Denisov does not agree that they take a disproportionate role in Russia’s foreign policy.

“The EEU is a functioning and rather clear mechanism. It is rather new and there are many initiatives of such kind in the world. There is a legislative base in place and I haven’t heard that the Russian government is planning to transform the EEU into a military alliance,” maintains Denisov.

It is important to keep in mind that Russia is not a part of China’s BRI initiative. The idea is that the BRI, when approaching the EEU border, transforms into an “alignment”, i.e. there is a conjunction between the EEU and the BRI. The purpose of the project is to promote trade between the parties.

Despite the declaration to align the EEU and the BRI, Russia faces obstacles in its attempts to create a common space on the Eurasian continent. One of the challenges that Russia has encountered is that China sees many of the integration projects as constraining and is very protective of its own initiative.

“The question is whether China considers itself a Eurasian power. The Russian word ‘prostranstvo’ (space) does not imply borders, since the Russian language has such expressions as outer ‘space’. However, according to some experts, China nevertheless considers Russia’s activities in Eurasia as attempts to contest China’s position,” explains Denisov.

Denisov believes that in order to avoid unnecessary competition between different integration initiatives, mutual recognition of each other’s interests in the region should be a priority for both Russia and China.

“The next integration step is a positive agenda of some kind, an agreement. Today, new institutions and hierarchies are not in demand, since they are perceived as an attempt of the initiator to dominate. Apparently, there is only one way: to use already existing platforms in order to create a network for cooperation.”

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, BRI. Picture: Shutterstock

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, BRI. Picture: Shutterstock

One characteristic feature of Chinese foreign policy is that Beijing strives to solve all political issues mainly through bilateral contacts. At the same time, China is starting to realize that it is not possible to carry out economic projects when important security issues in the regions are not tackled. One of the central questions is whether the countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States, CIS, can agree on a common stance towards China. Compared to the 1990’s, China has changed, as has the whole region. China has more tools of influence today, in particular when it comes to economic resources. For instance, Kazakhstan’s debt to Beijing has risen dramatically. This makes it difficult to unite the positions of Russia and the other CIS countries on the issue of cooperation with China. According to Denisov, the multilateral formats including China and several other parties can lead to a positive development:

“The more multilateral cooperation that includes China the better. Dialog is a precondition for a better understanding between different states and can prevent conflicts in the region.”

The road to a fully functioning Eurasian partnership including both Russia and China is long, although not impossible. One challenge is that Russia’s and China’s interests in Eurasia converge and diverge at the same time. It is easier for China to reach agreements with economically less powerful actors. Also, there are economic sectors that Russia would like to protect from Chinese influence. Another issue for the “Greater Eurasia” initiative is whether members of ASEAN would commit to it, since Chinese presence in this region raises many questions. A clear alternative is thus the development of a range of multilateral platforms, like APEC or ASEAN, so that as many countries as possible get a chance to participate and explain their views, concludes Denisov.

Igor Denisov is Senior Research Fellow at the Center for East Asian and Shanghai Cooperation Organization Studies, Institute for International Studies at the Russian Foreign Ministry’s MGIMO University.