Russia and Turkey: Similar yet opposite

Analysis. Vladimir Putin’s Russia and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Turkey increasingly look like sisters under the skin. Domestically authoritarian and internationally assertive, traditionally suspicious of the West’s designs and cold-shouldered by the United States and the European Union because of their growing illiberalism, Ankara and Moscow appear intent to forge a strategic relationship and challenge Western hegemony. Yet paradoxically, the similarities between the two Eurasian powers’ imperial strategic cultures make their seemingly flourishing entente fragile and fraught with potential conflict, writes UI Senior Fellow Igor Torbakov.

Publicerad: 2019-03-07

On November 19, 2018, at the end of the Erdoğan-Putin Istanbul meeting that took place after the ceremony marking the completion of TurkStream gas pipeline’s offshore section, Turkey’s president gave his Russian counterpart a curious gift. When they were about to part, Erdoğan handed Putin four exquisitely bound volumes – the Russian translation of Gogol’un İzinde (Following Gogol), a massive tetralogy by the leading Turkish author Alev Alatlı. The symbolic meaning of Erdogan’s bookish present appears to be much deeper than mere reflection of the Turkish strongman’s reading preferences, although he says he admires the author and has recently made her a member of the Presidential council on culture and arts policies.

In her epic work, Alatlı – a best-selling writer, prominent public intellectual and staunch supporter of Erdoğan’s policies – has created a complex and colorful tableau in which real events of Russian and Turkish history are intricately intertwined. In the novel’s staggering 2,000 pages, she revisits the works of Russian literary titans like Gogol, Dostoevsky, Nabokov and Solzhenitsyn, and interprets their insights in the context of Russia’s (and Turkey’s) turbulent transformations past and present.

At the heart of Alatlı’s narrative is the perennial clash of the two principal intellectual strands – Westernizing and nativist ones – and their quest for the “authentic” Russia. Readers follow Russia’s trials and tribulations through the eyes of the narrator (and Alatlı’s alter ego) – a Turkish Muslim female intellectual Güloya Gürelli – who actively participates in the heated Russian debates, being at the same time haunted by a related problem: where to find the “authentic” Turkey – in its Islamic past or rather in its quasi-European present?

Alev Alatlı. Photo: Shutterstock

Alev Alatlı. Photo: Shutterstock

The novel’s conclusion is unambiguous: the glory and grandeur of the historic Russia and historic Turkey should be sought not in the Enlightenment-based foundations of modern Western civilization with its cult of progress and unlimited consumption (as well as its pernicious tendencies toward cultural imperialism) but in the distinct spiritual principles of Russian and Turkish/Islamic civilizations respectively.

It would seem that with the Alatlı book Erdoğan sought to draw Putin’s attention to the striking similarities between Russia and Turkey. More specifically, his aim was to underscore that the Turkish-Russian relationship, which, in Erdoğan’s own words, has now reached its “peak,” rests not only on a whole raft of mutually beneficial trade and energy deals but also on a similar political-philosophic outlook.

At its core lies the vision of the world divided into distinct civilizations. The upshot of such a vision is threefold: 1) a just world order can only be a multipolar one; 2) no civilization has the right to usurp a hegemonic position in the international system; and 3) the non-Western civilizations (such as Turkey and Russia) are in the ascendant. Anti-Westernism and self-assertiveness are the crucial elements of this outlook. As Alatlı put it, “We are the second wave. We are the ones who have adopted Islam as an identity but have become so competent in playing chess with Westerners that we can beat them.”

Does Erdoğan have a point? The answer is: both yes and no. A comparative analysis of Russia’s and Turkey’s historical trajectories would indeed produce an astonishing image of their family resemblance. If we look at the persistence of the two countries’ imperial legacies, their continuous grappling with ethnic diversity and nation-building, the patterns of their modernization and democratization, as well as how Russia and Turkey historically related to and were perceived by Europe, we will see some intriguing similarities and numerous parallels.

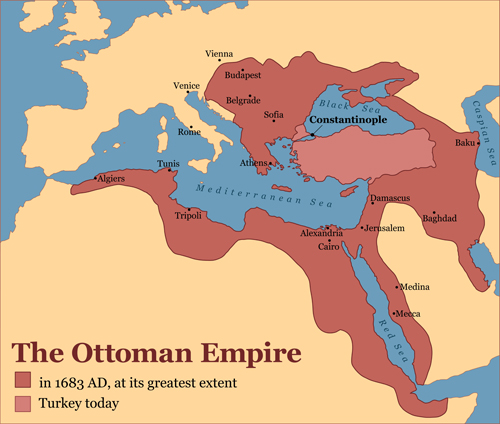

Map: Shutterstock

Map: Shutterstock

The drama of imperial collapse and difficulties of post-imperial readjustment are central for understanding the mindset of Turkey’s and Russia’s governing elites. The two countries are classical post-imperial states where the imperial past still powerfully influences Russia’s and Turkey’s present. While both countries’ governing elites insist that their strategy does not involve a restoration of empire, they are also quick to point out that Russia and Turkey are not some “ordinary nation-states” and like to talk about “privileged interests” in their strategic environment. The task of reintegrating — economically or otherwise — their immediate neighborhoods appears high on the two countries’ agenda. The popular notions of the greater Russkii Mir or the “Eurasian Union” and the idea of the historical “Ottoman sphere” seem to reflect the persistence of imperial imaginary in both countries.

In land-based empires, with their blurred borders between the national “core area” and the periphery, an overarching imperial identity stalls the development of ethnic- or civic-based nationalism and the emergence of nation-state. Following the collapse of the Romanov and Ottoman empires in the final year of World War I, the Soviet and Kemalist elites sought to resolve the tension between empire and nation that proved so fatal to the pre-war imperial polities.

Russian Bolsheviks and Turkish nationalists appeared to have chosen opposing strategies. While the Soviets attempted to deal with cultural diversity through constructing a sui generis communist “empire of nations” based on ethnic federalism, the Kemalists opted for Turkification aimed at the assimilation of national minorities. Yet in contemporary Turkey and Russia the process of nation-building has not been completed, as the very notions of “Turkishness” and “Russianness” are being vigorously contested. Notably, in both countries the concept of national unity is largely understood as state unity and all separatist forces are ruthlessly suppressed. Unlike the “post-modern” EU countries, which delegate powers both upwards and downwards, Turkey and Russia are still very “modern” in that they put a special premium on statist nationalism, centralization and sovereignty.

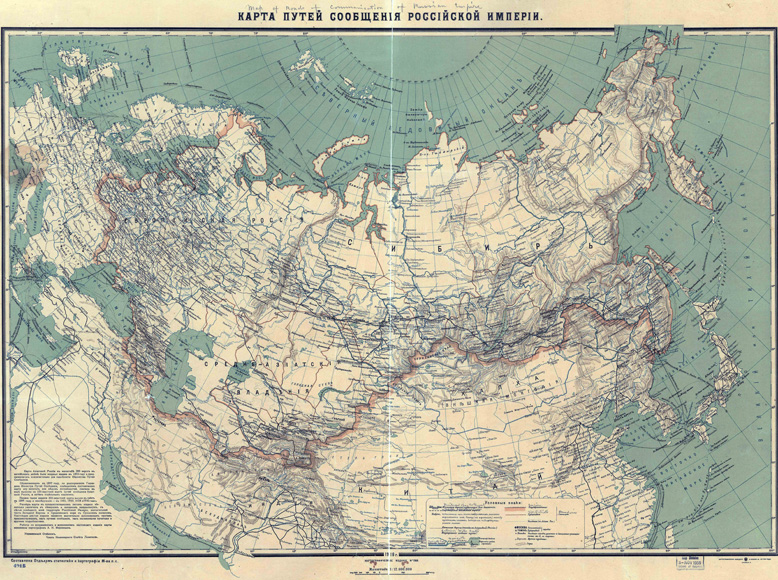

Map of railroads in The Russian Empire in 1916. Creative Commons

Map of railroads in The Russian Empire in 1916. Creative Commons

Furthermore, historically, Turkey and Russia displayed the distinct patterns of “alternative modernity.” Russia’s and Turkey’s mobilizational models were characterized by the enhanced role of the state, the relative weakness of domestic bourgeoisie (which has long been reflected in the latter’s subservient position vis-à-vis the state bureaucracy), the underdevelopment of independent economic actors, and the resultant feebleness of democratic institutions.

Yet these mutations of modernity were themselves affected by one key feature of political culture that Russia and Turkey appear to share and that predates both countries’ encounter with the technologically superior West. It is, in the apt formulation of the historian Carter Findley, “the sacralization of the institutions of rule and the concentration of power at the top and in the center.”

For its part, this autocratic tendency helped shape the image of Turkey and Russia as Europe’s others. According to the outstanding 19th century Russian historian Vasilii Kliuchevskii, the ways and mores in the Ottoman Empire and the Muscovite Tsardom — as seen by Western European diplomats, merchants and travelers — seemed quite similar: “They perceived both Muscovy and Turkey as the Oriental lands.” Despite the profound social changes that both countries have undergone over the last two centuries, European mass publics continue to perceive them as others.

One can argue that although there appears to be a significant dissimilarity in the two countries’ positions — unlike Russia, which considers itself equal to the EU as a whole, Turkey has become an EU candidate country and started negotiating for EU accession — this difference is being progressively eroded due to the comatose state of Turkey’s accession process. This paralysis effectively leaves Turkey and Russia basically on the same page, as Ankara would probably have to look for forms of association with the EU other than the full membership. This is not the only similarity, though. Significantly, both Turkey and Russia are themselves uncertain about their European identity as their heated domestic debates illustrate so well.

Eyup Sultan Mosquein Istanbul. Photo: Tatiana Zinchenko/Shutterstock

Eyup Sultan Mosquein Istanbul. Photo: Tatiana Zinchenko/Shutterstock

Turkey and Russia belong, of course, to different religious realms: the first is overwhelmingly Muslim, while the second is an Orthodox majority country. Yet there appear to be striking parallels in the ways Russians and Turks conceived of the relationship between religion and modernity throughout the 20th century. Turkish and Russian mobilizational models clearly saw religion as the enemy of modernity. Driven by the faith in reason, belief in progress and extreme forms of scientism, the Soviets and the Kemalists sought to undermine the grip of religion in their societies or even to suppress it altogether.

However, both Orthodox Christianity and Islam can be seen today as religions on the rise. The increasingly prominent role of religion has sparked a crucial debate in both societies on how a nation’s religion and culture correlate with its striving to become modern. Put simply, the question under discussion is: how does a particular religious denomination affect the country’s modernization? Does it facilitate social development or does it slow it down?

It is noteworthy that in both Russia and Turkey Max Weber’s famous works in the field of sociology of religion — in particular, his contention that Calvinist (and more widely, Protestant) religious ideas had a major impact on the social innovation and development of the economic system of the West — are being reappraised by contemporary Turkish and Russian conservative thinkers. First, they argue that the Western trajectory of modernization should not be seen as the only pathway to modernity, and, second, that their countries’ evolving modernities seek to realize particular institutional and ideological interpretation of the modern program according to their own cultural and religious codes.

The willingness of the growing numbers of Turkish and Russian elites to embrace traditional religion as well as their extolling indigenous cultural sources of development contribute to Turkey’s and Russia’s diminishing reliance on Western templates, and to their growing sense of strategic independence.

Turkish soldiers in historical military uniforms parade in Moscow. Photo: Trenkov/Shutterstock

Turkish soldiers in historical military uniforms parade in Moscow. Photo: Trenkov/Shutterstock

With its emphasis on cultural uniqueness and geopolitical autonomy — the concepts with a long pedigree in the Russian and Turkish political thought — a civilizational paradigm has become extremely popular with policy elites in both countries. Distinct civilizations and cultural coalitions are seen these days in Moscow and Ankara as the main units of international relations and principal building blocks of the emerging new world order.

A civilizational perspective has a strong appeal for contemporary Russian and Turkish elites. Rejecting the idea of linear progress makes irrelevant such tasks as “catching up with” or “superseding” the West – the objectives that have long eluded Russia’s and Turkey’s rulers. Instead, the argument goes, each individual civilization should focus on its own development and evolve according to its own logic and on the basis of its indigenous principles.

By the same token, the notion of “Western values” (and their universal applicability) also gets discredited. Each civilization possesses a unique set of values. “The rhetoric of the free world, human rights and democracy causes ‘westoxication,’” asserts the author Alatlı. “These attractively looking dishes are served to poor [non-Western] countries, which afterwards suffer from Western poisoning.” Neither Erdoğan nor Putin would seem to disagree with this contention.

Erdoğan and Putin in a ceremony in marking the completion of TurkStream gas pipeline’s offshore section in november 2018. Photo: Kremlin ru

Erdoğan and Putin in a ceremony in marking the completion of TurkStream gas pipeline’s offshore section in november 2018. Photo: Kremlin ru

Now, the big question is: can these deep-seated structural similarities, philosophical affinities as well as contemporary authoritarian, populist and illiberal characteristics of Erdoğan’s Turkey and Putin’s Russia serve as a solid foundation for a long-term strategic alliance between Ankara and Moscow?

Ironically, as both Putin and Erdoğan increasingly resort to civilizational discourse and imperial imaginary, with the Turkish president’s top aide musing about the likelihood of “the revival of the Turkish and Russian empires,” the prospect of establishing a viable Russo-Turkish Entente Cordiale does not look great. Empire’s political philosophy is one of universalism and exceptionalism. Empires do not have loyal friends or strategic allies; they have either enemies or dependencies.

Unlike nation-states with their clearly defined and fixed boundaries, empires are not status quo powers and are wary of the idea of strict borders, especially in the areas they regard as their strategic backyard. By contrast, the imperial/civilizational paradigm inevitably implies the notion of “frontier zones” – buffer territories over which historical empires have continuously fought. These zones fluctuated significantly over time. One important result of these fluctuations was the lack of well-defined boundaries between different ethnic groups. For Turkey and Russia, the mixed and mingled lands of the Caucasus, the Balkans, and the Middle East have historically constituted such frontier zones.

The narratives of the past, patterns of political imagination, historically conditioned values, symbols, traditions, and ideologies constitute what some scholars define as “strategic culture” that shapes decision-makers’ perspectives on their polity’s security and on international politics at large. Interactions between Turkey and Russia as neighboring land-based imperial rivals have strongly affected the formation of their respective strategic cultures. In Turkey’s case especially, notes the political scientist Malik Mufti, “fear of Russian expansionism – directly through war and indirectly through internal subversion of disgruntled minorities – emerged as an enduring legacy for Ottoman, then Turkish, strategists.”

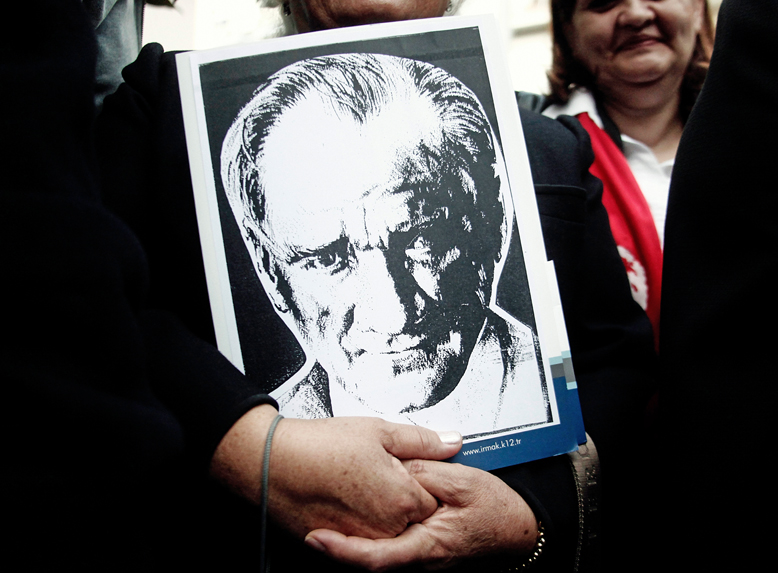

It is noteworthy that the only period when Moscow and Ankara had a decent relationship was in the 1920s-1930s, when, in the aftermath of WWI, imperial collapse, and internal conflicts, the two enfeebled countries consciously avoided imperial adventures, turned inward and focused on domestic transformations. Both the Turkish Kemalists and the Soviet Bolsheviks were mostly preoccupied with protection of the hard-won borders of their post-imperial polities and with carrying out unprecedentedly radical internal reforms. That was the context in which Republican strategic culture paradigm had emerged, together with its most famous tropes – “Peace at Home, Peace in the World” in Kemalist Turkey and “Socialism in One Country” in Stalinist Soviet Union.

Kemal Ataturk. Photo: Alexandros Michailidis/Shutterstock

Kemal Ataturk. Photo: Alexandros Michailidis/Shutterstock

Interestingly, it was also during this time that a renowned Russian legal scholar, Andrei N. Mandelshtam, sketched the contours of the future multipolar world order, in which Russia and Turkey might become members of the same cultural coalition. Writing in 1930, Mandelshtam (who was a trained Oriental Studies specialist and in 1898–1914 served at the Russian Imperial Embassy in Constantinople) put forward what he called the “future legal structure of the world” that he thought the humankind would eventually end up with. Along with the “Union of all peoples (League of Nations) that would take care of the common interests of the entire humankind,” Mandelshtam theorized, there would be also “large groups of states connected by common interests (e.g. European, American, British, and Russian groups).”

When he turned to the analysis of Russo-Turkish relations, Mandelshtam suggested that if the Turks had realized that their “cultural and economic interests were closer to Russia’s interests than to those of Europe and Asia,” Turkey “might become a member of the Russo-Turkish grouping that would have its own distinct physiognomy as the European and American groupings.” Maybe, he added, “Persia would also join this [Eurasian] grouping after a while.” In the 1930s, however, Mandelshtam’s scenario did not come to pass. The revival of Soviet imperial ambitions after 1945 immediately prompted Turkey to flee under the Western security umbrella and join NATO in 1952.

A halcyon era of the Russo-Turkish rapprochement in the 2000s – not unlike that of the 1920s-30s – was to a large extent conditioned by the persistence in both countries of versions of strategic culture that put a premium on the restrained international conduct. These days, however, both in Ankara and Moscow, the ruling elites seem to be operating within the Imperial strategic culture paradigm, readily deploying tropes like “New Turkey” and “Russian state-civilization” respectively. Yet while both the Turks and the Russians work assiduously to “compartmentalize” various aspects of their “multifaceted relationship,” the logic inherent in their imperial strategic cultures undermines the potential for building the genuinely good-neighborly and trust-based relations.

This is a paradox of Turkey’s and Russia’s family resemblance: the attempts of both sides to revive past imperial grandeur resurrect the specter of imperial rivalry and of the shatter zone in the “in between” borderlands. Notably, most of the issues that divide Moscow and Ankara today -- Crimea, Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, Kosovo, Cyprus, Syria -- broadly belong to the geography where the erstwhile empires of the Ottomans and the Romanovs clashed over several centuries.