Erdoğan's war in Syria – a path to disaster

Analysis. Turkey’s latest moves have put immense pressure on the EU and Russia, but it has nothing to do with neo-Ottomanism. Instead strong anti-Kurdish underpinnings and Turkish nationalism are the main drivers of Erdoğan’s foreign policy in Syria and elsewhere. This combined with the fact that Erdoğan is surrounded by an entourage of people who dare not tell him differently could mean Turkey is heading for disaster.

Publicerad: 2020-03-06

A prominent Lebanese analyst who is exclusively knowledgeable on Syria told me during a recent conversation that there is enormous confusion in the public opinion regarding Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's policy on Syria.

Turkey was virtually in war with Syria, and it could also be dragged into an armageddon with Syria's backer Russia over the contested Syrian province of Idlib. The hopes were pinned on the Erdoğan-Putin summit to be held on March 5 in Moscow to reach a ceasefire, to avert a war with broad implications on the international system, and to find an interim solution for the Idlib situation.

The picture is extremely complicated and confusing to understand. Adding to this complexity of the Syrian situation involving Turkey and Russia, the Turkish leadership, in a display of frustration perceivedly from the European Union's lack of support for the Syrian refugee pressure Turkey has been facing, announced that it will open its borders to Europe for the Syrian refugees who want to migrate to European countries.

On March 2, 2020, Erdoğan threatened the European countries in unequivocal terms: "The period of Turkey's unilateral self-sacrifice in relation to the refugees has come to an end. Since we have opened the borders, the number of refugees heading toward Europe has reached hundreds of thousands. This number will soon be in the millions," he said.

In such a convoluted crisis with multifaceted international magnitudes originated from the developments in Idlib, it became essential to understand President Erdoğan's game plan. It is a very daunting task, as he is notoriously enigmatic and unpredictable to a certain extent.

Migrants are waiting behind a fence by the Kastanies border gate at the Greek-Turkish border on March 2, 2020. Photo: Giannis Papanikos XTS157/AP/TT

Migrants are waiting behind a fence by the Kastanies border gate at the Greek-Turkish border on March 2, 2020. Photo: Giannis Papanikos XTS157/AP/TT

What happened?

The turning point for the dangerous escalation between Turkey and Russia’s proxy Syria with the potential to trigger a Turco-Russian military confrontation was an airstrike that killed at least 36 Turkish soldiers in Idlib, in the northwest of Syria, on February 27. The strike blamed on the Syrian air force by Turkey, but perpetrated by Russian fighter planes, exacted the highest death toll upon the Turkish military in any single day’s action in nearly 30 years. Russia disclaimed direct involvement but appeared to excuse the attack, saying the Turkish soldiers were in the company of “terrorists,” implying that they were with Syrian rebels, some with al-Qaeda connections, and enjoyed the military support of Turkey.

The airstrike that traumatized the Turkish public opinion was the dramatic outcome of the increasingly bloody clashes among Turkey, the Syrian regime in Damascus, and Russia over Idlib, the last stronghold of the Syrian rebels under the Turkish protective umbrella. In February 2020 alone, the Turkish casualties climbed to at least 53 in Idlib, which if continued at the same pace, would be unsustainable for Turkey’s delicate internal balance of power.

In Idlib, since April 2019, and more rapidly since December, the Russian-backed regime offensive was underway, and the offensive succeeded to retake swathes of Turkey-aligned rebel-held territory, forcing hundreds of thousands of civilians to flee.

Until this current crisis Turkey and Russia had established a partnership over Idlib according to a deal they signed in Sochi on September 17, 2018.

The Sochi Memorandum included 10 points. The Turkish-Russian deal envisaged the pacification of the al-Qaeda-affiliated Salafi/jihadist organizations using Idlib as a base to attack the Syrian government forces and the nearby Russian airbase. It aimed, as well, at demilitarizing Turkey-aligned Syrian rebels controlling swathes of territory in Idlib. Turkey would undertake that commitment, and Russia would prevent the Syrian government forces attacking Idlib to regain it by force. The Turco-Russian deal in Sochi mostly remained on paper.

Russia had a different interpretation of the Sochi deal than that of Erdoğan. For Russia, the main issue of the Sochi deal was getting rid of the “terrorists” based in Idlib, and Turkey did not or could not deliver its promises. Therefore, the offensive of the Syrian government forces backed by Russian airpower to clear the province from the Salafi/jihadist/Islamist terrorists was legitimate. Eventually, by the beginning of March 2020, the war between Turkey and Syria began, with the potential or prospect of a Turkish-Russian full-blown clash.

Stages of Erdoğanist foreign policy

How did Turkey, under the firm leadership of President Erdoğan, one time a close friend of Syria’s Bashar al-Assad and having enjoyed a functional partnership with Russia’s Vladimir Putin over Syria, end up where it is?

The answer partly lies with Erdoğan’s political style. Not only is he notoriously unpredictable and non-conventional, but the historical record of Turkey’s Syria policy is also a display of inconsistency since the advent to power in November 2002 of Erdoğan and his party AKP (the Turkish acronym of Justice and Development Party).

The AKP, considered to have moderate Islamist roots, was formed in 2001. Islamist Erdoğan, who surprisingly got elected with a small margin of the vote as the mayor of Istanbul in 1994, was sacked by Turkey’s secularist authorities who were under the influence of the secularist watchdog military and imprisoned for several months in 1999. Personally banned to run, Erdoğan led his newly-found party to electoral victory during a period when the Turkish political center had collapsed due to ineptness and severe economic and financial crisis. Erdoğan’s AKP, with a secure parliamentary majority, lifted the ban on Erdoğan, opening the way for him to become an MP in a by-election in 2003.

Tayyip Erdoğan, prime minister from March 2003 to August 2014, never lost an election. In August 2014, Erdoğan became the first directly elected president in the history of the Republic of Turkey, a portfolio he will hold until 2023, the year of 100th anniversary of the foundation of the republic. His record makes Erdoğan the longest-serving leader in the republican history exceeding that of Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the republic who served between 1923 and 1938.

The foreign policy of Turkey from 2003 to date, naturally, bears the strong mark of Tayyip Erdoğan, and Syria occupies a peculiar place in it. It could be seen basically in four different stages:

- The liberal period: Turkey’s foreign policy prioritizing the EU accession. It covers mainly the period from 2002 to 2011. During this period, Turkey made an opening to the Middle East by introducing soft power, primarily with trade and diplomacy. Syria became the mainstay of this policy. In this period, Tayyip Erdoğan and his wife developed a warm and emotional relationship with Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad and his wife.

- Disappointment with the EU and encouragement from the Arab Spring: The frustration with the EU for Erdoğan and his loyalists had begun in 2007 when Nicolas Sarkozy was elected president of France. Sarkozy, with Angela Merkel of Germany, sent signals that Turkey will never become a full member of the European Union. In 2011, at a time when the relations between the EU and Turkey was at a standstill, the Arab Spring saw the overthrow of the regimes in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya. With the Muslim Brotherhood coming to power, Erdoğan saw an ideological and political opportunity to project Turkey’s power in MENA (Middle East and North Africa). The winds of change knocked on the doors of Syria in March 2011. The Turkish leadership, predicting the ultimate downfall of the Assad regime in line with Tunisia and Egypt, changed course. The relations with the Syrian regime in Damascus was frozen in the fall of 2011; the diplomatic ties were suspended, the ambassadors were withdrawn. Turkey, departing from its traditionalist Middle East policy of non-involvement in the internal affairs of neighboring countries, assisted the formation of Syrian opposition under the umbrella organization Syrian National Council (SNC) based in Istanbul. It hosted the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood and supplied logistical support to various Islamist Syrian factions, some with extremist Salafi/jihadist tendencies, in cooperation with Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

- Prioritizing the Kurdish issue, rapprochement with Russia, drifting away from the United States: That period in Erdoğan’s Syria policy began roughly in July 2012. It is the date of withdrawal of the Syrian regime from the Kurdish-inhabited areas along the border with Turkey, and Kurdish autonomous administrations came into being replacing it.

- The uncertain new period: The year 2020 spelled the end of the exclusive relationship that was underway from 2016 to date between Turkey and Moscow.

Without knowing the timeline of Turkish involvement with Syria and its military engagement within the context of regional geopolitics, international relations, and with its unmistakable reference to the developments of Turkish domestic politics, it will be almost impossible to understand the trajectory of Erdoğan’s Syria policy.

Erdoğan’s Eurasianist deviation

The foreign policy performance of Erdoğan during the last years is an additional factor to understanding the enigma that was an integral part of his political identity. Especially since the year 2016, following the removal of its chief architect Ahmet Davutoğlu, Turkish foreign policy under the firm grip of Erdoğan diverted its traditional Western vocation and set on a pro-Eurasianist course. That meant Syria in focus while moving away from the West, taking steps to form a de facto axis primarily with Russia and, to a lesser extent, Iran, over Syria.

Erdoğan’s flirtation with Russia with the desire to change Turkey’s European vocation and replacing it with a Eurasianist one goes back to 2013. During a state visit to St.Petersburg in November 2013, at the joint press conference, he had said to Putin in front of the cameras, “Why don’t you let us into the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, so we [Turkey] would be liberated from the European Union.” It took three years more to set on that course.

Erdoğan had taken further dramatic steps in the second half of the year 2016. To restore the deteriorated relationship with Russia, he presented a public apology as had been demanded by Vladimir Putin through mainly second-track diplomatic channels.

After Turkey shot down a Russian Su-24 airplane on the Turkish-Syrian border in November 2015, Turkish-Russian relations reached their nadir. Russia steadily ramped up pressure on Erdoğan. In early March 2016, Russia’s permanent representative presented the UN Security Council with evidence alleging ties between the Turkish government and terrorist organizations. He primarily implied ISIS and al-Nusra Front (later and currently HTS-Hayat Tahrir al-Sham that controlled big swathes of the territory of Idlib), including involvement in illegal trade in oil. In April, Erdoğan sent mediators to Russia to discuss reconciliation with Putin. Several months later, in late June 2016, Erdoğan issued a letter of apology for the fighter jet incident.

In the aftermath of the apology, the relations between Turkey and Russia improved so rapidly that it led to speculations that Russia played a role in thwarting the coup attempt against Erdoğan in mid-July 2016. Putin, in the very early hours of the ongoing coup attempt, unequivocally stood up for Erdoğan, and the latter continuously blamed the United States and the European Union for remaining reluctant in supporting him.

Three weeks later, Erdoğan emboldened by the rapprochement with Russia, sent Turkish armed forces into Syria.

Migrants at Turkey's Pazarkule border gate, Edine, trying to enter Kastanies in Greece. Photo: Emrah Gurel/AP/TT

Migrants at Turkey's Pazarkule border gate, Edine, trying to enter Kastanies in Greece. Photo: Emrah Gurel/AP/TT

Turkish uniform and boots in Syria

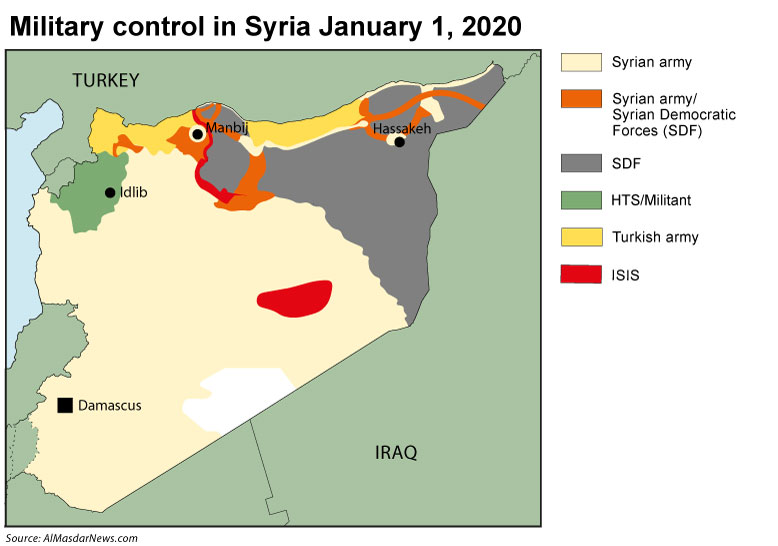

Turkey had its first military incursion into Syria, dubbed as Operation Euphrates Shield, lasted from August 24, 2016 to March 29, 2017. Turkey and Turkish-backed Syrian rebels managed to capture an area of 2,055 square kilometers. The operation would be impossible without the endorsement and connivance of Russia, which was establishing itself as the principal military player and a power broker in that part of Syria.

Thus, for Turkey’s drift from its traditional pro-Western foreign policy towards a new pro-Eurasianist orientation centered on privileged relations with Russia, the internal and external components became rife between 2016 and 2020. Syria is the showroom of this cardinal foreign policy change.

The Turkish invasion (Operation Olive Branch in the Turkish official parlance) of the historically and overwhelmingly Kurdish-populated northwestern corner of Syria, the district of Afrin of Aleppo province, demonstrated the level reached in Turkish-Russian partnership.

The Turkish military onslaught could never be materialized and fulfill its objectives without the green light given by Russia that opened the air space it controls for the Turkish air force. By letting Turkey into Afrin, which, as anticipated, resulted in the displacement of its Kurdish population, Russia, albeit tacitly, conspicuously prioritized Turkey over Syrian Kurds who generally were believed to be Russia’s proxies in Syria.

The third and overdue Turkish military excursion (Operation Pece Spring), targeting to dismantle the Kurdish self-rule in northeastern Syria, was launched on October 9, 2019. The Russians did nothing to deter Turkey from undertaking it.

The fourth Turkish military undertaking, as mentioned in the introduction of this article, was unleashed on March 1, 2020 in the Idlib province against Syrian government forces backed by Russia.

What is Turkey after in the Syrian imbroglio? The Western world, generally, entertains itself with a simple observation: All is the result of Erdoğan’s neo-Ottomanist ambitions.

From my angle, Erdoğan’s Syria policy has nothing to do at all with neo-Ottomanism. It should instead be envisaged as the foreign policy dimension of the Turkish autocratic nationalist regime gradually installed in Turkey during the second decade and especially in the second half of the second decade of the 21st century. With strong anti-Kurdish underpinnings, Turkish nationalism has become the main drive of Erdoğan’s foreign policy foremost in Syria and elsewhere. Given the ideological background of Erdoğan and his ruling party and its constituency, the overriding Turkish nationalist foreign policy exercise in Turkey had Islamist decorations as well. But all these do not make it neo-Ottomanism.

A noteworthy view in this regard is put forward by Professor Ömer Taşpınar, one of the leading Turkey analysts in Washington. He wrote to Asian Times on February 5, 2019: “Today, the real threat to Turkey’s Western and democratic orientation is no longer Islamization, but a broad-based Turkish nationalism and its frustration with liberalism and pluralism. . ..”

Nationalism can explain the modus operandi of Tayyip Erdoğan in Syria policy from August 2016, the date of the first Turkish military incursion. It is also interconnected with the internal political climate in Turkey in the wake of the botched coup. Parallel to relentless crackdown on the Kurds inside Turkey, the Erdoğan regime redefined the threat perception concerning Turkey’s security. In this regard, it prioritized the Syrian Kurd forces under PYD-YPG.

Erdoğan was committed to undoing the Kurdish autonomy in Syria. For that end, he sent the Turkish military into Syria, an audacious undertaking that signified a radical departure from the traditional Turkish foreign policy. The last time Turkey dispatched military troops across its borders to establish a quasi-permanent presence was in 1974 to Cyprus.

Defensive motives, expansionist impulses

In this regard, Erdoğan’s assertive foreign policy undertakings within Syria could be judged ideologically as nationalist rather than Islamist (or neo-Ottomanist). By the same token, and rather than having an expansionist objective aiming to acquire new territory to add to Turkey, it should be interpreted as defensive. It is defensive in the sense of forming the first line of defense not within Turkey itself but in the conflict zone off Turkey’s frontiers.

I was privy to a conversation, helping to understand Erdoğan’s mindset at the outset of the Syrian conflict. The Syrian conflict was its embryonic stage, and I spoke with then Prime Minister Erdoğan at the end of March 2011. At the time, he had cordial, even fraternal relations with the regime of Bashar al-Assad in Damascus. He responded to my question regarding the looming conflict in Syria. It was a confidential conversation. A year later, when he transformed into an irreconcilable adversary of Assad, I published our discussion in my book Mesopotamia Express – A Journey in History. The part of that confidential conversation will also be published in my upcoming book that is in the stage of printing, Turkey’s Mission Impossible, War and Peace with the Kurds, as below:

“Syria [is significant for us] as it is tantamount to Aleppo. Aleppo echoes Hatay [province of Turkey to the west of Aleppo, annexed in 1939, and which Syria still officially regards as its own.] Moreover, Syria is also Qamishli. There is no need to explain what Qamishli is.

I had not expected that response. I asked Erdoğan to elaborate. ‘That is to say,’ he continued, ‘we cannot allow a similar refugee flow as we experienced with the refugees coming from northern Iraq in 1991. We cannot establish our lines of defense within our territory.” He cut it there.”

The anecdote clearly illustrates the awareness of the geopolitical ramifications inherent in the Syrian conflict at the top echelons of power, even at the very beginning of it. Erdoğan was also concerned with the possibility of a refugee flow into Turkey. In private conversations, the officials at the highest level conceded to me that Turkey might be obliged to step into Syrian territory if the number of Syrian refugees amassed at Turkish borders exceeds 500,000. By March 2020, the number is close to 5 million and almost a million more people in Idlib witnessing a humanitarian catastrophe are knocking on Turkey’s closed border at Hatay province.

The dialogue with Erdoğan at the beginning of the Syrian conflict should demonstrate that the Turkish leader had no expansionist designs in Syria but had worries and was motivated more with defensive impulses.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (left) and Russian President Vladimir Putin talk during their meeting in Moscow Thursday, March 5, 2020. Photo: Pavel Golovkin, Pool/AP/TT

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (left) and Russian President Vladimir Putin talk during their meeting in Moscow Thursday, March 5, 2020. Photo: Pavel Golovkin, Pool/AP/TT

Whither disaster?

Whatever the defensive impulses of Erdoğan in 2011 and the expansionist tendencies manifested in 2019 were, they, in essence, were nothing but the reflections of inconsistencies of his Syria policy. In March 2020, unless Putin extends a helping hand for him, his Syria policy may well end up in disaster. It should never be forgotten that Turkey’s President Erdoğan is an autocrat surrounded by his hand-picked sycophants. At times of predicament that necessitates making crucial decisions, that is one of the worst situations a leader could find himself in. The brilliant veteran Turkish journalist Amberin Zaman in her Al-Monitor piece on February 27, quoting an Ankara-based source with close knowledge of Erdoğan’s inner circle, touched upon the same matter. With a cynical note she wrote, “Since becoming president, Erdoğan has surrounded himself with people who don’t dare to tell him, ‘You are making a mistake.’ Now he’s left with a circle of bootlickers who are mostly so ignorant they can’t even tell that he is making mistakes.”

Above anything else, it is Erdoğan himself who needs to be blamed for this. “Maverick, out-of-control authoritarian leaders – and here we are talking about Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey’s president – tend to think they know best about everything, and are fiercely intolerant of criticism. It is this hubris that has finally led Erdoğan and Turkey to the brink of disaster in Syria after nine years of bombastic threats, proxy conflict, and direct military intervention,” wrote Simon Tisdall on March 2 in The Guardian.

Erdoğan could not succeed in bringing Putin to Istanbul on March 5 to settle the differences over Syria. Instead, he took the road to Moscow to be received by Putin to negotiate on Syria.

As predicted, Erdoğan and Putin agreed only on an interim solution, a face-saving for the Turkish President for a while. According to many analysts and Turkey experts, the Erdoğan-Putin summit at Moscow spelled a diplomatic defeat for Erdoğan.

The fate of Erdoğan and the future of Turkey are as interconnected to Syria’s destiny as ever before.